Having spent the past few years on a busy international schedule Richard Perkins has purchased a farm in Sweden where he is establishing ridgedale PERMACULTURE. This is the first of a series of articles, first published in December 2013, looking at design considerations for this cold climate Permaculture site using the Keyline Scale of Permanence as a organizing framework, as well as an informative read for anyone interested.

The aesthetic curves of the Keyline layout at ridgedale PERMACULTURE

The popular and somewhat unique aspects of Keyline Design include the Keyline Plow & its patterned use for soil development and water conservation, combined with intelligent water harvesting, storage and irrigation. However, the SoP is a beneficial organizing pattern for Permaculture Design, which leads to the creation of aesthetic, harmonious and cooperative interactions between the farm and the landscape.

P.A. Yeoman’s Scale of Permanence

- Climate

- Landform

- Water

- Roads

- Trees

- Buildings

- Subdivisions

- Soil

Our Yeoman’s 6SB Plow fresh off the boat, summer 2013.

Planning in this manner means the most permanent aspects of the landscape are acknowledged and layout of farm systems is optimized before dealing with the more malleable aspects. This article will touch on climate and landform, which are almost unchangeable aspects of a landscape.

Site Specifics

The farm is situated three hour’s drive from Oslo, four hour’s from Stockholm and 3.5 hour’s from Gothenburg in the heart of Scandinavia.

- Latitude: 59°50’15” N, Longitude: 13°08’34” E,

- Land area of 10.6 ha (26.1 ac)

- Perimeter 1892m

- Elevation between 120 – 167m above sea level

- Cold Temperate/Humid Continental Climate

- Approx. 634 mm of rainfall per year, or 52.8 mm per month.

- Average 147 days per year with more than 0.1 mm of rainfall or 12.3 days with a quantity of rain, sleet, snow etc. per month.

- The driest weather is in February when an average of 31 mm of rainfall occurs.

- The wettest weather is in August when an average of 73 mm of rainfall occurs.

- The mean temperature is cool at 5.4 °C (41.7 °F)

- Mean monthly temperatures have a variation of 20.8 °C (37.4°F) The average daily temperature range/ variation is 7.9 °C (14.3 °F).

- The warmest month (July) is very mild having a mean temperature of 16.1 ° C (60.98 °F).

- February is the coldest month (slightly cold) having an average temperature of -4.7 ° C (23.54 °F).

- Average 120 days frost- free (1- 30 day variance)

- Southerly Aspect

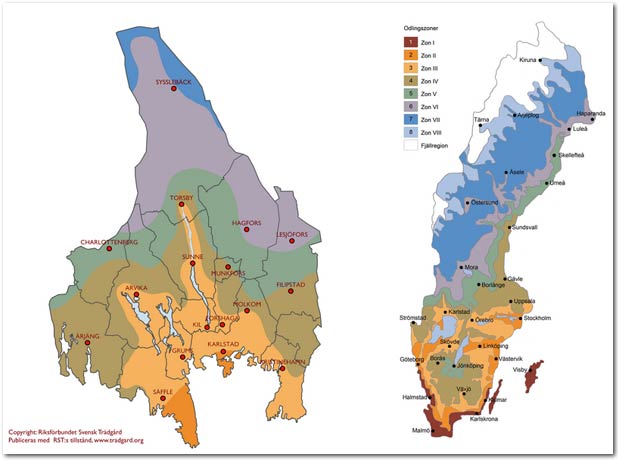

- Swedish Climate Zone 3- 4

- Wind, predominantly S but quite sheltered by surrounding forest

- Soil: Moderate Clay loam. Depth between 10- 30 cm with both sand (upper ridge) and clay subsoils 20- 300cm+

- 1.5 ha 90yr+Spruce plantation

- 0.2 ha 25 yr Spruce/ Larch/ Birch

Swedish Climate Zone with a zoom in on Varmland

(We are just outside Sunne in the centre of the zoom in image)

Cold climate design is all about leveraging micro-climates and heat sinks and at this latitude, where light is the limiting factor, maximizing photosynthesis captured and reflecting light with heat sinks (ie, water bodies) is ideal. Through appropriate wind breaking, orientation and functional interconnections it is possible to jump a whole climate zone.

10kW Biomass Gasifier & Genset |

With such a short frost-free growing season we have less perennial species available at our disposal than some of you might be familiar with, however I can think of at least 180 solid cropping perennials for this climate zone (we are profiling five a week currently on our blog). Options like biomass gasifiers which can heat and power lighting for greenhouses as well as the farm will prove very handy in a country like ours where most farms have access to forest. In fact, Sweden was a leader of this technology during the WWII era, when a lot of cars ran on wood gasification. We will look at innovative uses of appropriate energy in the final article as we are trying to close the loops and make the farm as future-proof as possible regarding oil and resource inputs.

The number of farmers in Sweden is in decline as bigger enterprises buy out small farms suffocated by the economy, high taxation and costs of production and changing consumer habits. It is interesting to consider the landscape — now predominantly fast-growing “vertical desert” monoculture spruce — which was once more diverse in tree species.

The open grasslands are (often only) kept open by subsidized mowing by machines where herbivores are strangely absent. From what I’ve seen of the farms I have been working at here, as well as our own, the pasture is degrading back to moss. Over the summer I’ve being taking people out to monitor supposedly “healthy” pastures with large proportions of moss and bare ground. They look green at least! This is indicative of a combination of water logging, poor nutrient cycling and highly compacted clays — we couldn’t get our penetrometer more than a couple of centimetres into the soil anywhere we visited over this dry summer. The grasses also suffer from lack of grazing impact in this negative spiral, and typically the response is to plow and seed for a quick-fix relief. This never addresses the root cause, nor supports the future resource base we are managing holistically towards.

Brief overview of primary landscape components

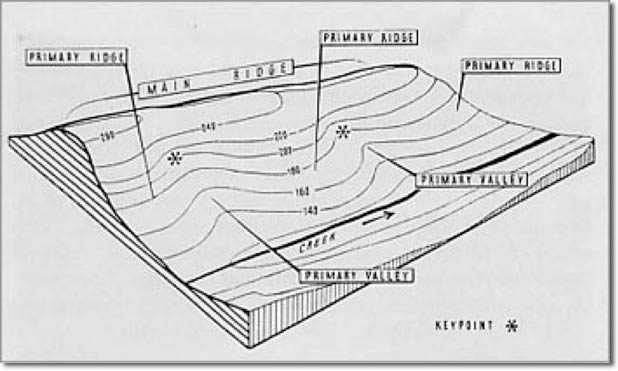

The three primary landscape components: From The Geographical Basis of Keyline

At the top of a primary valley you find the steepest part of a landscape. P.A. Yeoman’s identified the Keypoint (marked in stars on the picture above) as a point where a short steep slope changes to flatter and shallower slope in the primary valley. This is also known as the point of inflection (imagine looking at a cross section, the shape of the landscape profile would turn from convex to concave) or the point of deposition; this is where finer particles such as clays usually begin to aggregate in a valley. The Keyline is the contour line that runs through the Keypoint to the edges of the primary valley. Where a ridge ends and a valley begins can be identified on a topographic map as it too has an inflection where you could say the contours change from concave to convex. What you find if you look at a map is that Keypoints in primary valleys descend toward the sea — part of what allows the eloquent Keyline patterning of larger landscapes like P.A. Yeomans developed at Yobarnie outside Sydney.

The Keypoint is usually the highest place to economically store water in earthen dams in a landscape, unless there are saddles in the main ridge. As water naturally leads to this point on its S-shaped flow through the landscape (water always flows perpendicular to contour) and due to the shape of the valley, this is usually where the earth resources exist for this type of construction, as well as being a shape with optimal an capacity:soil moving ratio. This high placement in the landscape forms the backbone of gravity fed irrigation systems. We do not have these features at ridgedale, and we do not have the water issues of the brittle landscapes, but we will be making effective use of water and keeping it under very good control without using power.

It is worth noting that whilst a lot of properties do not have any significant landscape features such as these, the principles, affects and design sequence of Keyline design remains highly effective.

Part of the significance of these primary landscape components is understanding how water moves in relationship to land shape. Water is the basis of all life on earth, and the limiting factor in most agricultural production. Managing water effectively is crucial for future-proof resilient food systems. What you notice if you get a map out is that the valleys are a small percentage of any landscape, while ridges make up the majority of the landscape. In Yeoman’s work, He observed how valleys tend to have adequate water and that ridges tend to dry out, rendering them unproductive. That was in a Mediterranean climate. We are in a very different setting. Following this patterning is still very useful in our scenario as it can help alleviate wet spots, hold water on the ridges longer, accelerate soil building, aide tree planting and allow better infiltration of summer and autumn rains amongst other benefits.

Landform at ridgedale PERMACULTURE

Design following the pattern of the landscape, not imposing onto it.

Keyline subsoil pattern guide shown in purple, with adequate machine turning and permanent

fencing already marked in. Subsoiling and later tree strips will follow this geometry.

In some landscapes, where primary landscape components are present, establishing the plow pattern is based on following parallel to the Keyline up and down the valley, and on the ridges following the lowest contours parallel up the ridge. Combined, this creates a pattern that is off contour, save the Keyline, and leads downhill from valley center to ridge center. This can also be approximated by feel, which is more likely on smaller properties and when primary landscape features are not present, but still following the basic premise.

Basic topographic overview (not accurate enough for planning here with 10m contour intervals) describing the undulating ridge/dale formation |

Here in Sweden when the snow melts in the spring, farmers are mostly concerned with drainage of their landscape. A lot of resources and capital are spent to this end, and yet this summer we had almost no rain for several months and the pastures suffered. Building carbon in the soil is the cheapest way to store water, with 1 particle of humus able to hold on average 4 parts water. Our focus is on building deeper living soils that can deal with the excess water, plus retain it for the dry summer period. Integrated perennial crop strips (see first image) throughout the pasture on the Keyline layout will also help with excess water along with a whole heap of other benefits, such as microclimate, forage, cropping and nutrient cycling. We are designing to deal with the core problem, not address symptoms. Ultimately designing for resiliency is going to be cheaper, organic by default and requires an increase in production! Combined with holistically managed grazing this degraded farm is in for total transformation.

We also have heavy compaction — not great for our pasture, and certainly not good for planting trees directly into. This land was once known for its apples, and our neighbor can remember a lot of apples here 50 years ago. The soil is also thin here in places, down to 15cm. The neighbor asked why I would want to pull a subsoil plow through below the topsoil into the “dead mineral” layers? Well, the reason is at least threefold. Firstly, the only difference between topsoil and subsoil is life, air and water. We can begin to address all that with a simple pass of the plow, and can accelerate our impact by applying compost teas, biofertilisers, etc. A regenerative agriculture could be defined as one that, at the very least, builds soil. All land-based production is founded upon growing soil, which remediates so many of our issues.

Secondly, we lift compaction, and one of the advantages of the Yeoman’s Plow over generic subsoilers is the effective explosive subsoil shattering that occurs up to 30cm from the point, due to the angle of the foot and the tip dynamics. We encourage deeper rooting to allow water to sink; and following this geometry to hold water on the ridges for longer. Timing is important here, and we will look at this when we get to soil.

Thirdly, we can make high quality tree beds for better establishment of our perennial tree and shrub crops. Long-lived and slow-growing organisms are valuable, and, just like children, a good start sets up the foundation for the rest of life! After subsoiling the fields we will power-harrow the tree strips as a basic weed disturbance, then deep rip the tree lanes, with a rotavator bed-former attached (two shanks spaced widely to accommodate staggered plantings). Whilst we will get a profusion of grasses coming back we will seed a diverse array of support plants for the intensive tree and shrub plantings (which will be spot mulched with woody material to help the soil food web begin shifting to a more optimal fungi:bacterial ratio.) This pattern cultivation will allow us to continue our soil development work in the pasture strips between the trees.

Ripped and mounded tree beds (Photo courtesy Darren J Doherty)

One very nice aspect of this property is the two perennial streams flowing through the site, which mean we will be able to have flowing, living water distributed anywhere on the farm without using electricity or oil to pump it. We do not have the option for earthen dams in the landscape that could cover all our water needs through gravity feed, but we can run a RAM pump to cover that, and I know where to find the best quality units going. More about water in the next post….

Originally published here.