My personal journey into home energy reduction began with taking stock of past energy use as reported on my utility bills. I quickly migrated toward reading the meters directly to gauge the impact of particular activities. What I learned from our gas meter shocked me, and ultimately led to our single-biggest energy-saving behavioral shift. I’ve already ruined any hope of suspense in the title of the post, but just how bad does something have to be before I’ll resort to a word like “evil?” And how bad are your own demons? Ah—now you can’t wait to find out!

Gas Gauges and Units

We must first confront the asinine measurement and units scheme of the natural gas delivery system. At least it’s asinine in the U.S. For one thing, the billing units are Therms. One Therm is 100,000 Btu, or 1.055×108 J, equating to 29.3 kWh. My main beef with the Therm is that the way my utility bill is formatted, my gas usage in Therms is printed within a few millimeters of my electricity usage in kWh. Since one may be directly converted to the other (both are units of energy), why not use kWh for both!? Not only is the kilowatt-hour already in common use in the U.S., it’s a metric measure shared by the rest of the world.

More importantly, putting gas usage in terms of kWh would immediately allow comparisons between energy usage from gas vs. electricity. As it is, there may be only a few dozen people in the country who habitually make the comparison. While we’re at it, we should demand that the utility bill report how much fossil fuel resource and how much CO2 is is associated with each expenditure. This becomes important in a side-by-side comparison because roughly three times the electrical energy delivered to your house is consumed in fossil fuel thermal energy, the bulk of which is waste heat. But this is another battle for another day.

The second misfortune about our measurement scheme is that we locked into cubic feet for the metering. I suppose we got lucky that electricity is measured in a metric unit—the kWh—so perhaps I am pushing it to whine about the use of an Imperial unit in the U.S. Sure, I’d prefer an internationally recognized unit, but a more significant gripe is that cubic feet is not itself an energy measure. Then again, oil is measured in barrels—even though the oil we use never touches a barrel—and coal is measured in tons that may have anywhere from 5000 to 8000 kWh/ton depending on the grade. At least the conversion between cubic feet and Therms is pretty easy: one hundred cubic feet (hcf) of gas contains 1.02 Therms of energy. I’ll forgive you if you just call it an even Therm (does my gas meter measure volume to 2% accuracy anyway?).

The third annoyance with the metering scheme is that the analog meters I have experienced have dials for which a full turn represents 0.5 cf, 2.0 cf, 1000 cf, 10,000 cf, and so on. Did you notice the gap? That gap makes it very difficult to do meaningful monitoring of home usage—which may be partly deliberate, I sometimes think. But we’ll push on and discuss how to use the meter for measuring pilot lights and their implications.

Measuring the Slow Burn

Below are two photos of my gas meter, taken exactly an hour apart, when no activities in the house demanded gas (water heater idle; no cooking; no home heating).

At lower left is the half-cubic-foot-per-turn dial, followed by the two cubic feet dial to its right. Both advance counter-clockwise. Over the course of one hour, the 2 cf dial advanced approximately two tick marks, indicating something like 0.4 cf in an hour. The ½ cf dial almost makes a full turn—perhaps 0.88 turns, corresponding to 0.44 cf/hr, in approximate agreement with the 2 cf dial. Naturally, the next-smallest dial, at 1000 cf per turn, does not budge discernibly. Without my telling you that the 2 cf dial has not made a full turn, there would be no way to know. Thus monitoring the gas meter requires vigilance and awareness of gas usage within the house. It’s easy to botch it.

At lower left is the half-cubic-foot-per-turn dial, followed by the two cubic feet dial to its right. Both advance counter-clockwise. Over the course of one hour, the 2 cf dial advanced approximately two tick marks, indicating something like 0.4 cf in an hour. The ½ cf dial almost makes a full turn—perhaps 0.88 turns, corresponding to 0.44 cf/hr, in approximate agreement with the 2 cf dial. Naturally, the next-smallest dial, at 1000 cf per turn, does not budge discernibly. Without my telling you that the 2 cf dial has not made a full turn, there would be no way to know. Thus monitoring the gas meter requires vigilance and awareness of gas usage within the house. It’s easy to botch it.

Converting the volume measure to energy units, we can express 0.44 cf/hr as 0.0045 Therms/hr, or 0.131 kWh/h, otherwise known as 0.131 kW (~130 W). Over a month, this racks up about 100 kWh of energy, which is no insignificant outlay.

The following table may help to navigate the various conversions involved in interpreting your gas dial. The first two entries are for complete turns of the two fine-scale dials. The last two entries are for turn rates; the final one expressed as how long it takes the ½ cf dial to make a turn at a usage rate of 10,000 Btu/hr. Many gas appliances in the U.S. (stoves, heaters, etc.) are rated in terms of Btu/hr, and 10,000 Btu/hr is a convenient baseline against which to scale appliance ratings. For instance, water heaters are often in the range of 30,000–40,000 Btu/hr, and home furnaces may be something like 80,000 Btu/hr. So for instance, a water heater at 30,000 Btu/hr would make the ½ cf dial turn once per minute.

| On Dial | Therms | Btu | Metric |

| 1 turn of ½ cf | 0.0051 | 510 | 0.15 kWh |

| 1 turn of 2 cf | 0.0204 | 2040 | 0.60 kWh |

| 1 cf/hr | 7.5 Th/mo | 1020 Btu/hr | 299 W |

| 184 sec/½cf | 0.1 Th/hr | 10,000 Btu/hr | 2930 W |

My First Encounter

In the spring of 2007, when I first gazed at the gas gauges, I was renting a condominium that used gas for only two things: hot water, and home heating. During a day when neither service was being utilized, I observed the 2 cf dial to be making 0.72 turns per hour, or 1.44 cf/hr. That adds up to 1050 cf/month, or 10.7 Therms per month (equivalent to 314 kWh/mo). At the time, I paid $1.30 per Therm, amounting to $14/month or about $170/yr just to run two pilot lights. That’s a lot of burritos, folks.

More distressing was the comparison to our annual gas demand, which averaged 28 Therms/month, dropping to 15 Therms/month during the summer months. Thus, our two pilot lights accounted for 40% of our total gas usage, and over 70% of our summertime gas usage! Outrageous!

Having uncovered this ugly truth, I promptly shut off the furnace pilot light, since we were unlikely to need heating any more that year. In doing so, I found its contribution to be 7.3 Therm/mo, or about $10/mo, and twice as large as that of the (remaining) hot water heater’s pilot. Shutting off my furnace pilot light therefore resulted in halving my summertime natural gas usage. That’s a big win. Not some few percent sliver, as is typical of efficiency improvements.

Pleased with our summer savings, we decided to hold off on re-lighting the pilot light the next fall until we simply could no longer tolerate the cold in the condo. That day never came. So discovering just how wasteful the furnace pilot light was unlocked a path to energy reduction on a large scale. How we cope without heat (in San Diego, granted) is a story for another time.

Over-eager Pilot Light

In my current house, as indicated in the photos and associated numbers above, the hot water heater’s pilot light consumes about 0.44 cf/hr, or 3.3 Therm/mo. This is pretty comparable to the old condo’s hot water heater, so is probably pretty typical.

This summer, I outfitted our hot water heater with thermochron iButtons to learn when the heater came on in order to get a sense for how much natural gas was being used to provide our hot water. I had one sensor on the cold water intake, one on the hot water output, and one on the flue chimney to sense when the unit fired up to heat a new batch of water.

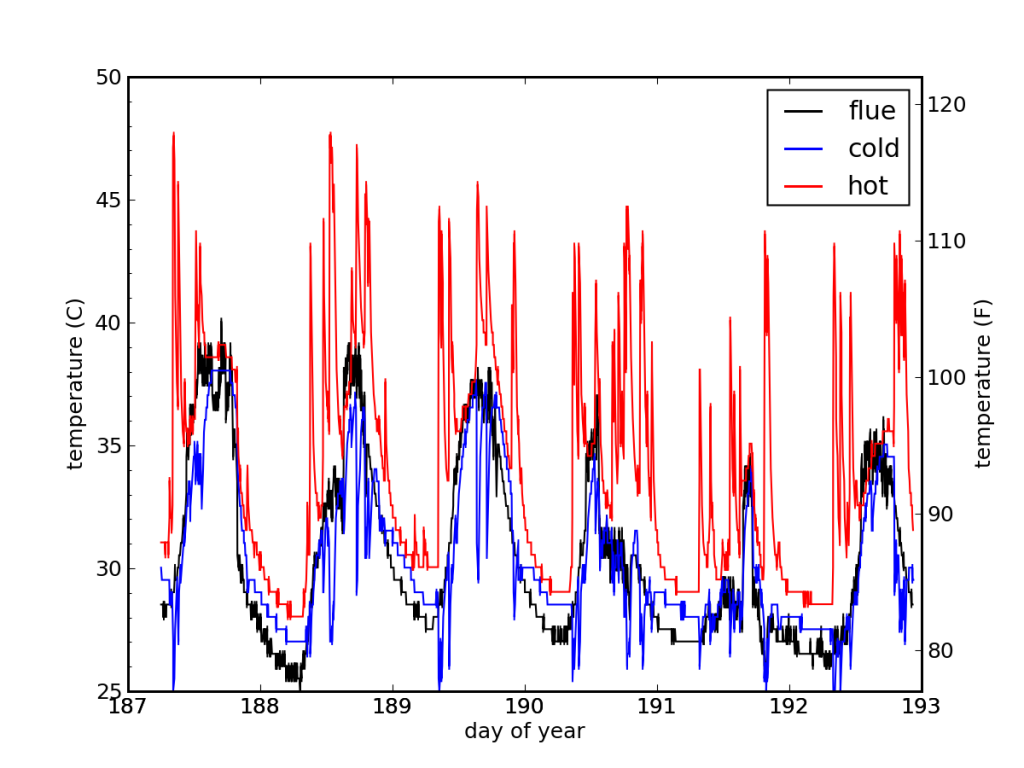

Over a six day period, what I found was that the heater never fired up! This is despite normal (albeit light) use of hot water for showers, washing dishes, etc. The plot below shows the measurements.

The flue temperature, in black, would have shot up off the plot if the heater had fired up. As it is, the flue temperature effectively provides a measurement of ambient temperature in our garage during this (hot) period. Hot water access is frequent, as seen by red spikes—accompanied by downward-going blue spikes as cool water is drawn into the unit. Based on measurements over a different period, the average temperature of the flue within the uninsulated, sun-beaten garage tends to be substantially hotter than the external temperature, by about 8°C (15°F).

The flue temperature, in black, would have shot up off the plot if the heater had fired up. As it is, the flue temperature effectively provides a measurement of ambient temperature in our garage during this (hot) period. Hot water access is frequent, as seen by red spikes—accompanied by downward-going blue spikes as cool water is drawn into the unit. Based on measurements over a different period, the average temperature of the flue within the uninsulated, sun-beaten garage tends to be substantially hotter than the external temperature, by about 8°C (15°F).

But the amazing thing is that the pilot light alone is providing enough heat to keep us in hot water during the summer months. How can this be true?

My wife and I are pretty sparing in our use of hot water: an average of five minutes per day at about 6 liters/min for showering (we’re each on a more-or-less two-day schedule), plus maybe a comparable amount for other uses. So let’s call it 60 liters per day (about 15 gallons). From the difference between the downward blue spikes and the upward red spikes in the figure, it looks like we’re heating water by 20°C during this period. Taking 4184 J to raise the temperature of one liter (kg) of water 1°C—in accordance with the definition of a kilocalorie—we require 5 MJ per day to heat our water.

From above, we see that my pilot light uses natural gas energy at a rate of 130 W. Over one day, this comes to about 11 MJ of energy. So we can easily accommodate our modest 5 MJ demand for hot water based on the steady expenditure from the pilot light. Of course there are losses due to heat escaping through the not-perfectly-insulated walls of the hot water tank and other paths. But we can use this investigation to conclude that such losses do not much exceed something like 50% given the 5 vs. 11 MJ matchup.

The Rub

So that’s kind-of cool that our hot water demand is below the level provided by the pilot light during summer. On the flip side, we lose regulation of the hot water temperature.

Normally, the hot water heater kicks on when the water temperature gets below the set-point. If the gas is never fired up, it means that our water never gets this cold. In fact, we find that our water is often too hot during summer. And it does no good if we turn down the thermostat: the pilot light conspires with the ambient temperature to determine the water temperature, and we have no way to turn the pilot light down.

So I would prefer a water heater with no pilot light (using electronic ignition like the seldom-used furnace in our new home), giving me control over the temperature set-point, and therefore how much gas we use. Or alternatively, a hot-on-demand system may similarly avoid wasted gas if it does not employ a pilot light. As it is, we are victims to our pilot light during the summer.

Of course other considerations keep me from rushing out to get a replacement water heater (embodied energy and expense to consider). Ideally, I’d like to move in the direction of solar hot water with natural gas backup. I am tempted to build the system myself—because it’s low-tech enough that I probably can, it would be cheaper to do it on my own, and I would learn a lot from the process.

Beyond Pilot Lights

Another profitable activity is to monitor the dials when a gas-consumer is on: furnace, hot water, stove, oven, etc. Not only can you confirm or discover the usage rate (often visible on a label in Btu/hr, for instance), but once calibrated you can use simple timing to tally gas usage. For example, if you know that it takes 20 seconds for the ½ cf dial to make a full turn when the furnace is on, and the furnace tends to stay on for 15 minutes at a time, then you know that each furnace cycle consumes 0.23 Therms, or about 7 kWh of energy.

What’s on Your Meter

I encourage you to check out your natural gas meter to learn how quickly you burn through gas 24/7 during quiescent times. I was truly surprised by what I found, and the behavioral changes fostered by this knowledge have had a tremendous impact on our home’s natural gas resource footprint.

Greater awareness of our resource usage (via measurement, metering, data) will collectively lead to smarter choices in the future. Many of our products are driven by consumer choice—informed to varying degrees. We need to educate ourselves and our friends on how to read, interpret, and act on the information available to us. If enough people were aware of pilot light pitfalls—as I have become—I imagine they would be more quickly phased out in favor of electronic ignition. Such a transformation is not without challenges (safety, failure, etc.), but it is not a stretch to imagine more widespread adoption of a technology that already has substantial penetration into peoples’ homes.

So when you are looking to replace a hot water heater or furnace, take the opportunity to kill the pilot light: and help rid the world of one more evil.

Originally posted here.